|

|

|||

|

||||

| Web Sites, Documents and Articles >> Hartford Courant News Articles > | ||

|

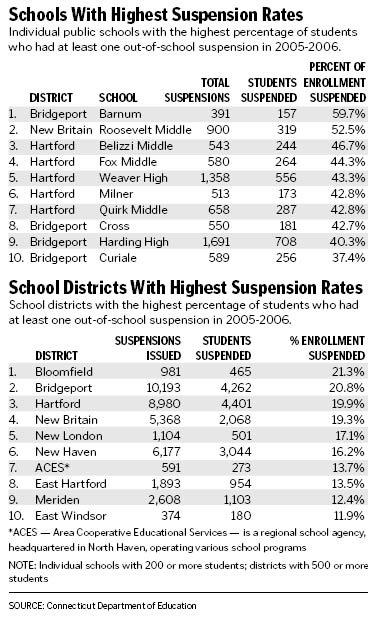

A Punishing School Debate Bill Would Put Limits On Sending Kids Home May 2, 2007 Some of Connecticut's most troubled public schools suspended misbehaving students so often last year that more than one-third of their students were thrown out at least once, state figures show.

One elementary school in Bridgeport issued out-of-school suspensions to 60 percent of its students - some of them several times. The bill, which passed unanimously in the House of Representatives a week ago, would require schools to provide alternative in-school suspension programs in most cases. The proposal is pending in the Senate. The measure pits those who argue that out-of-school suspensions are counter-productive against a broad cross-section of school officials. If passed, the bill would mean a radical change in Connecticut, where public schools issued more than 77,000 out-of-school suspensions in 2005-06 to everyone from pre-kindergartners to high school seniors - an average of about 80 suspensions per school, according to data submitted by school districts to the state Department of Education. "Those numbers are, from my perspective, far too high," said state Rep. Andrew Fleischmann, D-West Hartford, co-chairman of the General Assembly's education committee and a key sponsor of the bill. Although schools routinely issue out-of-school suspensions for potentially dangerous matters such as fighting or bullying, they also have handed out tens of thousands of suspensions for offenses such as talking back to teachers, skipping class, leaving school grounds or being tardy, statistics show. "It's an outmoded model of discipline," Fleischmann said. "I don't think it's good public policy that a 9-year-old who's behaving badly should spend three days out of school thinking about it." The idea of restricting out-of-school suspensions also has won support from others, including children's advocacy groups. "I think out-of-school suspension is a poor choice for both the student and the community," said Elaine Zimmerman, executive director of the state Commission on Children. "When children are told they are not wanted in school, they figure out a purpose and role outside of school, and most likely that role is not good." But Fleischmann's proposal has run into opposition from school officials, who say schools - not the legislature - should have the final say on how to curb bad behavior. "I think in-school suspension is an alternative, but to basically tie the hands of administrators ... is a poor idea," said Dennis Carrithers, assistant executive director of the Connecticut Association of Schools, an organization representing school principals. The bill is also opposed by the Connecticut Association of Boards of Education. In Hartford, educators have created in-school suspension rooms, set up Saturday classes and experimented with community service work as alternatives this year in an effort to reduce the number of suspensions, Superintendent of Schools Steven J. Adamowski said. Milner School, an elementary school with one of the state's highest suspension rates, has seen a 30 percent decline in out-of-school suspensions so far this year, he said. Nevertheless, Adamowski called the proposed law "a very bad idea." The pending legislation would allow schools to issue out-of-school suspensions only to students who pose a significant danger to people or property or a "disruption of the educational process" - provisions Adamowski described as ambiguous. "It will be interpreted 166 different ways, and there'll be 14 lawsuits," he said. "Students will be placed at risk, and attorneys will make a lot of money." Some educators also say the creation or expansion of in-school suspension programs would require additional staffing, adding to the cost. New Haven public schools, for example, have 11 in-school suspension workers but have asked state lawmakers for 36 more, enough to cover all of the city's schools, at an additional annual cost of nearly $2.2 million. New Haven's Hillhouse High School has a small in-school suspension program and runs other programs to reach troubled or truant students, Principal Lonnie Garris Jr. said. But out-of-school suspensions should be available as a last resort, he said. Because some children receive multiple suspensions, the number handed out at a few schools exceeds the number of students enrolled, according to state data. The district is working with the University of Connecticut on a program designed to encourage better behavior, including working with troubled students on anger management and social skills, said Superintendent of Schools John J. Ramos. At most schools, it is still more common to order misbehaving students out of school, but some are sending fewer students home by creating or expanding in-school alternatives. In Manchester, for example, officials say an in-school behavior intervention program has sharply reduced the number of out-of-school suspensions at Manchester High School. The rules are straightforward at the high school's Behavior Intervention Room: No talking. Follow directions. Do homework. Study "attitude packets" on matters such as anger control. "It sucks," said one 16-year-old boy serving a three-day suspension for skipping an after-school detention he got for showing up late to science class. "I can't wait to get out of here." But the school still sends students home for offenses such as fighting, insubordination or bringing alcohol onto school grounds. "If you eliminate out-of-school suspension, what do you propose?" Principal Donald W. Sierakowski asked. "We have people who are sent to school on court order and don't go to class. What's the answer to that?"

|

||

| Last update:

September 25, 2012 |

|

||

|